Balancing Habitat

Balancing Habitat: Lithium and boron are two examples of crucial minerals essential in reducing our planet’s carbon footprint for industries such as defence, automotive, construction, aviation, and aerospace. It is challenging to preserve the natural environment when starting new mines to extract these resources. How do companies such as Rio Tinto and Ioneer manage this dilemma and obtain the permits necessary in their respective locations?

Boron, Lithium – Sustainable Mining

Sustainable Mining for Green Energy

To make energy transition possible, provide clean energy, and reduce carbon emissions, vast amounts of lithium and, increasingly, boron is required in battery power. As for battery production increases in the US, it would be beneficial to have a domestic supply. Nevada’s only operating lithium mine produces 5,000 tonnes of lithium per year and exports much of it. The U.S. Ioneer plans to make four times that amount annually.

Mining and production of lithium and boron for strategic industries certainly offers enormous advantages, but species’ environmental degradation and extinction cannot be overlooked. Thus, there is a constant tussle between the mining companies and environmental protection agencies concerning new mining projects.

The Need for Critical Minerals

There are many benefits to mining minerals such as boron and lithium. Besides the obvious economic catalyst generating employment, such minerals support eco-friendly alternative energy sources. For example, lithium is essential for reducing climate risk and advanced battery production for EVs.

But it is becoming increasingly challenging to keep up with the demand for critical minerals. This makes battery costs more expensive when electric cars are rapidly used to reduce climate risk.

New mining projects are catching the attention of environmentalists who say the project can cause significant damage to the environment. There is an acute example of this in Nevada, where Ioneer, a large mineral resources company, opposes its latest lithium extraction project.

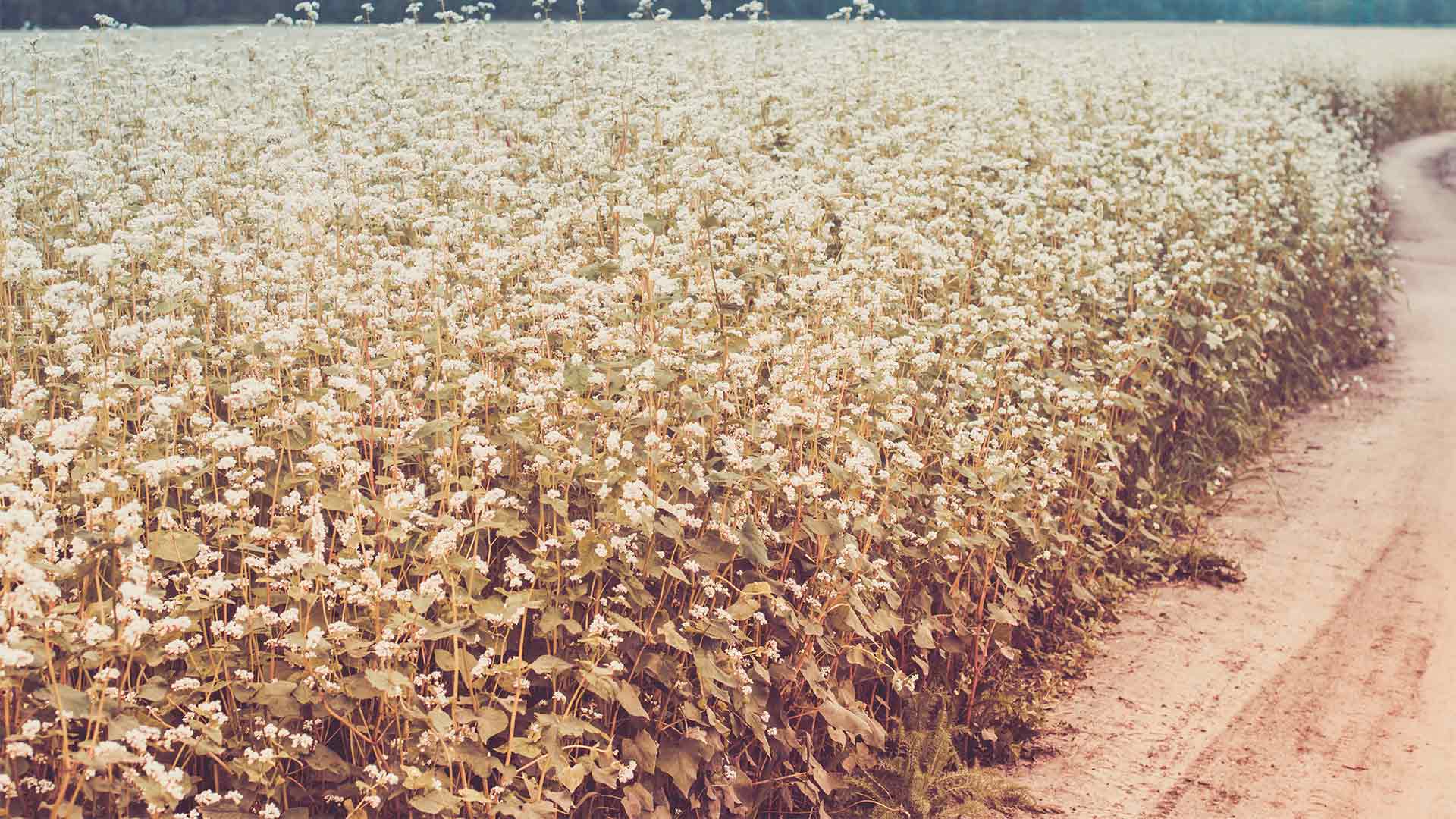

Ioneer, Wild Buckwheat Flowers, and the Rhyolite Ridge Project

The Rhyolite Ridge project happens to be home to a rare small yellow in a remote part of Nevada, four hours north of Las Vegas. It occupies an entire chunk of federally owned land about the size of two football fields. This land is the location of Ioneer, an Australian mining firm, proposed a lithium mining operation, which could produce enough lithium every year to power 400,000 electric cars.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service will decide whether or not to include the wildflower, Tiehm’s wild buckwheat, on the Endangered Species List. The Bureau of Land Management will make the final decision on whether Ioneer’s proposal for a mine can be approved. This could potentially destroy 90% of the habitat. This is just one example of a continuing challenge: How fast can we accelerate the energy transition if it threatens our environment?

This simple plant has a dull grey appearance. However, it will briefly bloom in spring after it rains. The small yellow flowers are a sign of its maturity. It is one of the hundreds of wild species of buckwheat.

These plants are related to the crop used to make pancake flour. It was discovered by Jerry Tiehm, a botanist at the New York Botanical Garden. He was on a hike through the West, looking for new plants. It appears that the plant evolved to only grow on the lithium-rich soil of the region.

As this site is one of several locations globally with large quantities of lithium and boron, the mining company plans to produce more boron than it produces lithium. Although lithium is an essential ingredient in electric cars and renewable energy storage batteries, boron is also a significant component of the energy transition.

Ioneer also points out that boric acids are used in magnets in electric cars or wind turbines. The company can mine both lithium and boron simultaneously, which helps reduce the production cost.

The unique adaptation of the plant to the clay, boron, and lithium on the site led to a study by the mining company concluding that it couldn’t possibly be relocated. Ironically, the Fish and Wildlife Service relied heavily upon the study to suggest that the flower be designated endangered late last year.

The Center for Biological Diversity filed a petition to protect the flower in 2019 when the study was starting. It sued BLM and Ioneer to halt exploration activities.

Patrick Donnelly, Nevada’s director for the Center for Biological Diversity (a non-profit that has been fighting to save the flower for over three years), states;

“The plant is in critical danger of becoming extinct. This mine would decimate almost all of its habitat as just one person with a bulldozer could eradicate the entire species.”

In 2019, a UN report estimated that 1,000,000 species were at risk of extinction due to various human-caused causes.

Donnelly was first informed about the plant by a Bureau of Land Management whistleblower in 2018. Ioneer applied for permits to explore the land. This was according to Dan Patterson, an environmental protection specialist who claims BLM knew the location contained rare buckwheat, yet work proceeded. Patterson then filed a complaint claiming that BLM rushed projects through without following environmental laws.

Recently, the government issued a directive urging “increased activity at all levels in the supply chain” for restorative materials like lithium. Currently, lithium is imported more than produced in the United States.

Climate change is one of the major drivers. The mining company argues that supporting the transition to clean energy will help protect the rare plant. It already suffers from climate effects such as drought. Mining can also directly destroy the plant’s habitat.

Ioneer – Current Status

Ioneer is having difficulty obtaining the permits. Ioneer claims it can protect plants by mining around them with a small buffer area. Still, the Center for Biological Diversity points out that the mining company plans to expand beyond a “starter mine” and into an area that would destroy all but one plant population.

Ioneer rejected the proposal of a buffer zone measuring one mile. Donnelly reiterates that “we, as an organization, are not opposed to lithium production. We have a whole group of people who fight every day for electric cars and battery storage.” (The organization has a safety climate transport campaign and a climate law institute.)

The Ioneer site is not the only one in dispute. A nearby large lithium mine with an estimated $3.9billion worth of the mineral is also under contention. It is threatening groundwater, streams, and species of trout. Mining can cause damage to the earth, not just rare flowers.

Other Projects in the Spotlight

Besides Ioneer, other companies such as Rio Tinto, are actively developing lithium and boron reserves for production to satisfy growing demand and experiencing the same challenges.

Rio Tinto – Problems in Serbia

Rio Tinto has also run into severe problems while developing its Serbian lithium mine. After protests from the Serbian community, Rio Tinto’s Jadar lithium mine was shut down. The backlash is due to the risk of environmental damage, habitat loss, water pollution, forced displacement that the project was set to cause.

Alternative Paths to Supply

As mining companies seek to pacify environmental concerns, other methods for extracting lithium are being considered. A standard method for producing lithium is to use substantial evaporation tanks but can cause other environmental problems.

Alternatively, recycling batteries may eventually supply some of this demand. Further, direct lithium extraction is a new technique that extracts lithium from underground saltwater. But this can reduce environmental damage. One pilot project in Clayton Valley, Nevada, will soon test this approach.

Future batteries could be made from cheaper materials like zinc, but this material is already insufficient and doesn’t require a lot of new mining.

Donnelly states, “I believe we need lithium. It’s not obvious that we need open-pit lithium mining. We don’t need lithium mines in open pits that cause species to die. This is not a green technology. It’s simply that we continue to do business the same way that brought us to where we are today. Because we are driving species extinct, we’re at the edge of ecological collapse and a climate crisis. It’s time to find a new way to do business.”